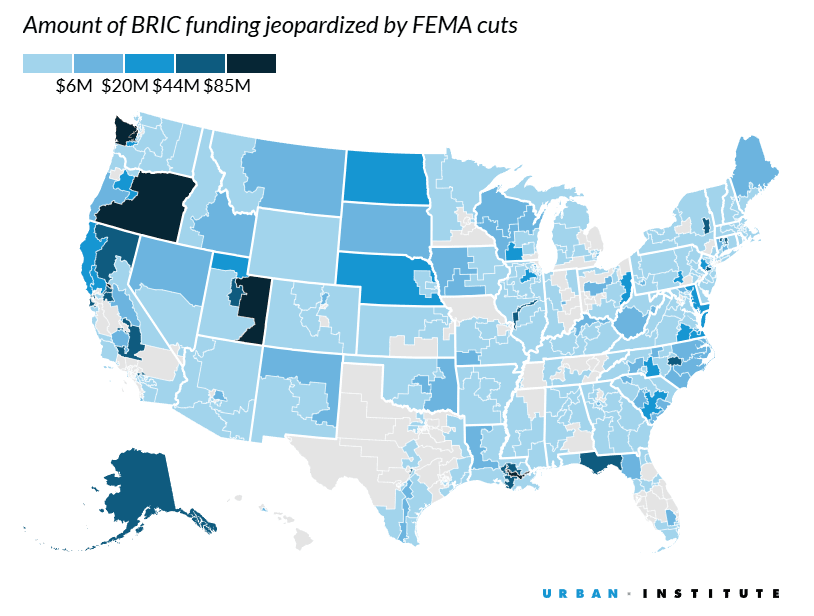

Last week, the executives of 20 states filed a lawsuit against the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and the United States of America, alleging that the shutdown of the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities Program (BRIC) was unlawful. The sudden cancellation of the BRIC program put $3.3 billion in federal funding to states at-risk, for a wide variety of projects focused on reducing the future costs of disasters. It is one of a series of moves by the Trump Administration to move the federal government away from hazard mitigation spending. In related news, the president has not approved requests for Hazard Mitigation Grant Program funding since February, and FEMA has not released a notice of funding opportunity for the Flood Mitigation Assistance Program for the current fiscal year.

The suit alleges that the cancellation of the BRIC program is unlawful, for three reasons:

That the termination of the program directly contradicts Congress’s statutory direction to FEMA and DHS to prioritize hazard mitigation, and therefore violates principles of the separation of powers;

That the refusal of FEMA and DHS to spend Congressionally appropriated funds violates Article I of the constitution, i.e. Congress’s power of the purse; and

That the individuals (formerly Cameron Hamilton and currently David Richardson) taking such steps at FEMA in their role as Acting Administrators were not lawfully appointed and therefore lack the authority to do so.

The lawsuit is the latest in a series of efforts by lawmakers to get the BRIC program reinstated and previously announced funds awarded, and represents a new front in the ongoing conflict over the future of FEMA.

The lawsuit is a fascinating read for anyone who is a student of disaster management or interested in the broader question of whether the President has the authority to significantly change the way the federal government supports state and local governments with their emergency management function. I wanted to share a few highlights that stood out to me as I reviewed the lawsuit:

The description of the background and history of hazard mitigation is a tidy read and a helpful reminder of the overwhelmingly bi-partisan support for the Disaster Mitigation Act (2000) and subsequent changes to the country’s hazard mitigation programs, including the Disaster Recovery Reform Act (2018) that led to the establishment of the BRIC program.

Citing the National Institute of Building Sciences, the lawsuit claims that investments in hazard mitigation have been “wildly successful” and helped avoid nearly $150 billion in disaster costs.

The lawsuit talks at length about 6 U.S. Code § 316 ‘Preserving the Federal Emergency Management Agency,’ which requires that FEMA be maintained as a distinct entity within DHS and that the DHS secretary not be allowed to “substantially or significantly reduce…the authorities, responsibilities, or function of [FEMA] or the capability of [FEMA] to perform those missions, authorities, responsibilities.” In short, the lawsuit alleges that only Congress can alter FEMA’s focus on hazard mitigation or reduce its ability to carry out its mitigation function.

For those of us who experienced Hurricane Katrina in an emergency management capacity, it is fascinating to see just how many of the safeguards that were enacted after that event are allegedly being violated by the current Administration, including the minimum professional requirements for the Administrator. Somewhere Michael Brown and Patrick Rhode’s ears are burning.

Paragraph 117 gets to the heart of the immediate issue, in my view, which is the tremendous harm that the sudden cancellation of the BRIC program is doing to the states and communities where those funds had already been applied for and won. Anyone who works on complex community-based projects knows of the tremendous amount of time, effort, emotional energy, relationship building, and even money that has already been spent by the time a grant is awarded. Putting aside the importance of mitigation generally, and the future of federally supported hazard mitigation specifically, the ‘rug pull’ nature of the cancellation of BRIC is deeply troubling. The lawsuit summarizes numerous projects that are now in limbo, from dune restoration projects in Maine to improving the capacity of building inspectors in Michigan.

Loper Bright makes its first appearance in paragraph 191, where the lawsuit alleges that DHS and FEMA effectively exceeded the legislation that created their offices, by gutting their Congressionally directed hazard mitigation function.

I am very far from being a lawyer, legal expert, or even regular watcher of Law and Order. But if this lawsuit against FEMA and DHS becomes the vehicle for settling the larger question of whether the Executive branch can simply not spend money appropriated by Congress, my heart will sing a little bit because many more people - in legal circles, the media, etc. - will be knowledgeable about FEMA and how it operates.

Not surprisingly, nearly all of the plaintiff states are led by Democratic governors, save one (Vermont)